Thursday 27.02.20

GOT TO LOVE A CR VIDEO

The more and more I have watched Craig the more I like him. He’s seems a nice guy and down to earth at the same time as being pretty informative in a relaxed way. If you haven’t checked him out, then give this video a watch and then subscribe to his channel as he’s got some great content.

Fordy

I was at work earlier this week and found myself demonstrating a resting squat; the ( unlucky!) person opposite me was in equal measures surprised and impressed but what I found shocking was their insistence that if they ‘ ever got down they would never get back up.’

I was at work earlier this week and found myself demonstrating a resting squat; the ( unlucky!) person opposite me was in equal measures surprised and impressed but what I found shocking was their insistence that if they ‘ ever got down they would never get back up.’

Being of Asian origin and having travelled extensively I am comfortable with this position and indeed it has been imperative faced with squat toilet facilities but in the west it is considered neither particularly attractive nor necessary unless perhaps camping.

The science however is mounting up and the fact is that making time to regularly take up this position helps stretch out tight hip flexors, the lower back, engage the core, protect the pelvic floor and when used as part of a dynamic movement strengthens the quads – ie undoing the relentless damage we are doing to ourselves through modern lifestyle trends, occupations and choices.

Shawn Stevenson explains more in his excellent article , ‘ The Resting Squat – How Squatting Makes You More Human’ which I have taken the liberty of quoting below:

The science is stacking up, and word is out that sitting for prolonged periods is devastating to our health. Former NASA scientist, Dr. Joan Vernikos, has compared sitting in a chair for prolonged periods to being weightless in space. This is due to the fact that the muscles, bones, joints, and other tissues aren’t supporting themselves naturally any longer. This newly dubbed “Sitting Disease has been shown to impact your blood pressure, blood sugar, and your ability to burn fat.

It’s not that sitting is bad. It’s more so how we’re sitting that’s really smacking our health around right now. The human body was never designed to sit in an awkward 90 degree position with certain muscles completely shutting off, while others are being dramatically over-stressed.

Gluteus Minimus

Sitting triggers your butt muscles to do absolutely nothing. They completely shut off and get used to not “activating” normally. This deranges your ability to walk, run, jump, stand up, sit down, and pretty much any other activity you can think of. Your glute muscles become limp and no longer fire properly when they are deconditioned from sitting too much.

Nil Abs

Your abs will be closer to soft-serve ice cream than a well-defined washboard if you’re sitting too often. Your abdominals actually help to hold you upright, but when you sit back in a chair they no longer have to work, and the battle of the bulge can take place. Your abs will quickly lose their tone and strength if you totally take them out of the equation by sitting.

Tight Hips

Unlike Shakira, your hips will be lying to you and everyone else when you try to exert yourself. Hip mobility and functionality is critical to all basic human movement patterns. Your hips provide stability and balance, and lack of mobility here is one of the major causes of serious injury.

Thinning Bones

It’s now understood that the largest contributing factor to poor bone density is lack of activity. Your bones need resistance to drive nutrients into them to trigger development. Sitting too often will lead to bonier bones, plus at heightened risk of disease and injury.

Back strain

People who sit more often are at greater risk of herniating their lumbar spinal discs. Sitting in chairs is synonymous with having “shortened” hip flexors. A large muscle called the psoas is a major hip flexor muscle that runs through the abdominal cavity. When the psoas is short (or tightened) from sitting too much, it pulls the upper lumbar spine forward which puts you out of alignment. Your upper body now rests on your ischial tuberosity (sitting bones) instead of being distributed along the arch of the spine. This is a leading cause of back pain and overall loss of function.

Bowel dysfunction

Sohrabi et al in their article

(Middle East J Dig Dis. 2012 Jan; 4(1): 23–27, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4017696/)

state that’’ the usual way to pass a stool, even in Western countries until a century ago and still today in many places, involves a position where the thighs are pressed against the abdominal wall and this is believed to assist stool evacuation.” There is indeed scientific evidence that squatting results is faster and more complete defecation helping us understand how it could prevent bowel diseases such as diverticulosis.

Microbiologist Guilia Enders concurs in her book , Charming Bowels , that we can evacuate more efficiently when we squat

This is because the closure mechanism of the gut is not designed to “open the hatch completely” when we’re sitting down or standing up: it’s like a kinked hose. Squatting is far more natural and puts less pressure on our bottoms. She says: “1.2 billion people around the world who squat have almost no incidence of diverticulosis and fewer problems with piles. We in the west, on the other hand, squeeze our gut tissue until it comes out of our bottoms.” Piles. Lovely.

What is a resting squat and why is it important?

Conventional sitting puts your weight onto another object by placing your butt on it and turning many critical muscles off. A resting squat is a posture where you squat down fully, lowering your hips towards the ground and your weight is equally distributed and controlled by your body.

For countless ages throughout time, human beings have been able to crouch all the way down into a resting squat for relaxing, working, cooking, communing, and even for using the bathroom. For babies and children it is the most natural position to assume .

If you can’t get down into the full resting position of a flat-footed squat, it’s time that you start working on it. If you don’t, you are dramatically limiting your mobility and ability to function at an optimal level. Start slow and use something to support yourself as you lower down. Trainer Debbie Atkins at Rev5 showed me a brilliant trick whereby as you lower yourself back and down you wriggle your toes – don’t ask me why but it works.

Wednesday 26.02.20

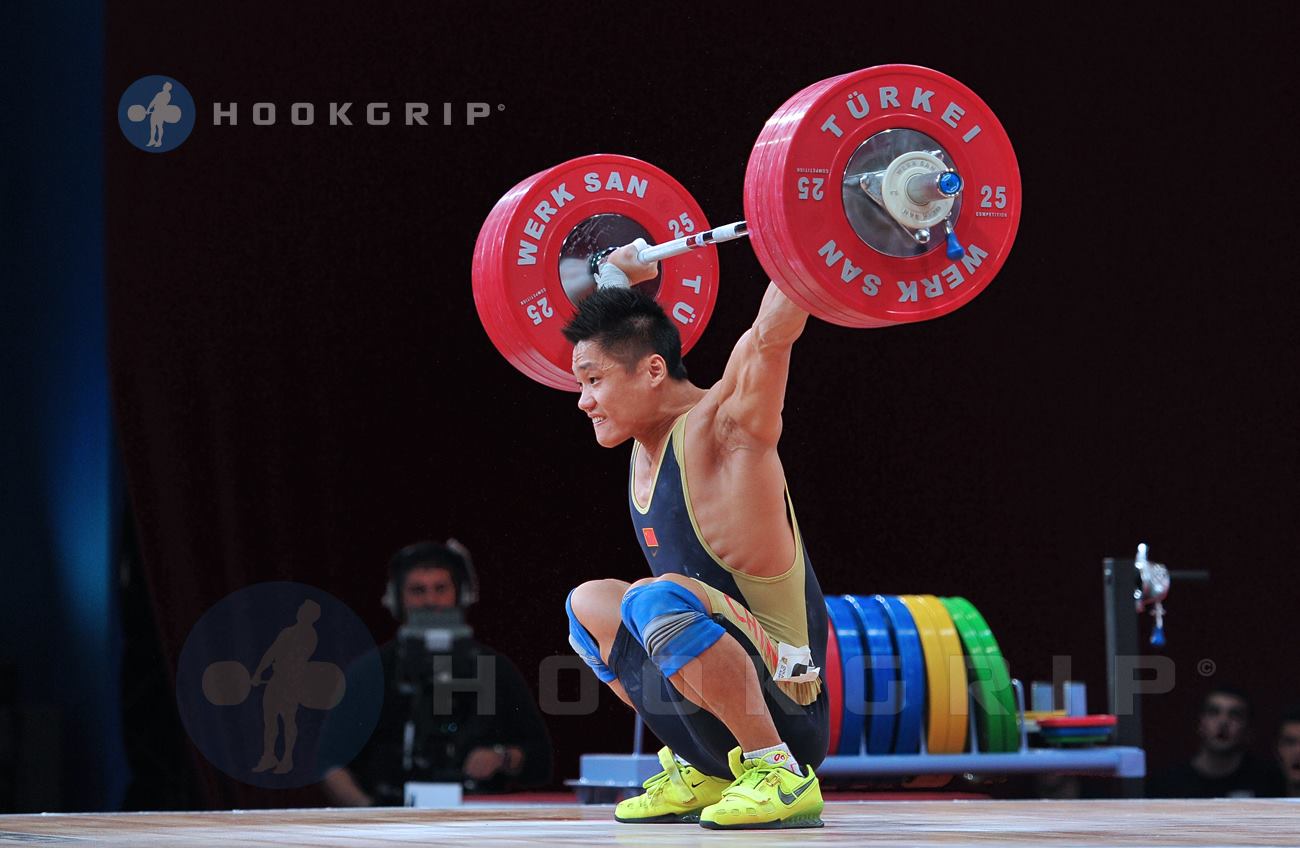

OHS

Over Head Squat. Think of it as a check of your mobility rather than just a really difficult version of a squat. The video opposite is great to look at why everyone should pretty much start every workout with a basic OHS to check that your feeling your mobility before going into your session.

Fordy

PERFECTING THE OVERHEAD SQUAT

Prior to the turn of the century, the overhead squat was primarily used by competitive weightlifters. Olympic weightlifting coaches use the overhead squat as a teaching progression for novice athletes. The overhead squat is used to strengthen the bottom position of a barbell snatch.

Since the recent boom in CrossFit, the use of the overhead squat has become more wide spread. It has been transformed into a staple exercise for training for many sports and has even been used in competition.

In order to perform this lift correctly, an athlete must have a high level of coordination, balance and mobility.

BAR OR PVC PIPE?

For inexperienced athletes or young children first learning to overhead squat, a barbell may be too heavy. For this reason, a lightweight PVC pipe or a broomstick can be used in place.

To find a proper grip with a PVC pipe that has no markings, try this simple method. Stand tall and pull your elbows out to the side. Your arms should end up in a 90-degree “L” position. Measure the distance between your right and left hand. Now mark that distance on the PVC pipe. Place your index finger on this line when grasping the pipe during the overhead squat.

When transitioning to the bar, athletes will usually take their grip a few inches from the end of the bar. This will be the same grip taken for the barbell snatch lift. Athletes with longer arms may need to take a grip almost to the end of the barbell, near the collars. Those with shorter arms may only need to place their grip around the outer notch of the bar.

THE SET UP

To start, hold the barbell on your upper back. This will be the same starting position as the high-bar back squat. After un-racking the barbell properly, the weight will need to be hoisted to the overhead position. This can be done in a number of ways depending on the amount of weight on the barbell and the individual preference of the lifter.

When first learning how to perform the overhead squat most coaches will teach a simple push-press to hoist the barbell to the overhead position. Once the weight increases to a significant load, a push-jerk or split-jerk is recommended for experienced weightlifters.

To start the push-press, pull the your elbows underneath the bar. This will place your arms in an efficient position to drive the barbell upwards. The hands should be at a snatch-grip width.

Next, take and hold a large breath. Brace your core muscles as if about to receive a punch to the stomach. Stabilizing the core through proper breathing and bracing allows your body to generate tremendous power for the rest of the lift. The dip & drive movement is then used to push the barbell overhead.

Drop your hips straight down a few inches while keeping your torso in a vertical position. A cue that is often used to maintain this straight dip is to imagine the feeling of your back sliding down a wall. If the hips drive backwards during the dip it will cause the chest to push forward. This will set you up to push the barbell forward into a bad overhead position.

During the controlled dip, the knees should be kept in proper alignment with the feet. This will allow for an efficient transfer of power from the legs to the arms during the push. If the knees collapse inwards on the dip, you will limit the potential upward driving power you can create with your legs.

After the dip is performed, push the barbell straight up by extending the hips, knees, and ankles in a powerful motion. The barbell should end up in a stable overhead position just over the back of your neck.

Here’s a great demonstration of the dip and drive movement to position the bar into an overhead position from Catalyst Athletics.

Your head can be pushed forward slightly to allow for this stable position. Be careful not to push the head too far forward! This will cause the chest to lean forward excessively and throw you off balance.

To keep the barbell overhead in a firm position the elbows should be completely locked out. You will have a difficult time keeping the barbell from wavering around if the elbows are not completely straight.

In this overhead position, the barbell should rest in the center of the palm. The wrists should be slightly extended. This is a position of stability that will not cause too much stress to the wrist joint. Do NOT try and keep a neutral straight wrist during an overhead squat!

Make sure to gaze straight forward or slightly upward. This will place the neck in a neutral position and limit any unwanted stresses. Looking upwards excessively or down towards your feet can throw you off balance.

THE DESCENT

Once you have stabilized the bar overhead, it’s time to start the descent. Push your hips back slightly to engage the posterior chain. As you begin your squat, think about sitting your hips onto your heels. This cue helps limit a large hip hinge that can throw you off balance. Control the descent to full depth.

The bar should always remain aligned over the middle of your foot for balance and stability. Proper technique is critical as a missed lift can lead to injury. If at any time the lift becomes unstable, push the bar forward or backwards and dump the bar to the ground. Both are completely safe alternatives for missing a weight. I recommend using bumper plates whenever doing overhead squats. Be aware of your surroundings.

Here’s another example of an overhead squat from Catalyst Athletics.

THE BOTTOM POSITION

The knees should be allowed to translate forward over the toes at the deepest part of this squat. This will allow you to maintain the desired vertical trunk position to keep the bar overhead.

THE ASCENT

The hips and chest should rise at the same rate during the ascent of the squat. If the hips rise fast and the chest stays forward, the barbell will drift towards your toes likely causing you to drop the weight.

Once you’ve come to a stable standing position, slowly control the bar down to the “shelf” position on your upper back. Letting the bar drop too quickly can lead to serious injury to the neck. If the weight is heavy, a slight dip can lessen the intensity of receiving the bar.

OVERHEAD SQUAT SEQUENCE

- Establish a safe starting position. The barbell should be resting on the upper traps (as with the high-bar back squat) with the elbows pulled under the barbell.

- Create a rigid trunk by taking a big breath and holding it tight. (Verbal cue: big breath & core tight).

- Use a controlled dip & drive to push the bar into an overhead position (Verbal cue: slide your back down a wall and drive upwards with power)

- Stabilize the barbell (Verbal cue: drive your hands to the ceiling & lock your elbows out).

- Use a slight hip hinge to engage the posterior chain.

- Remain balanced by keeping the bar positioned over the mid-foot the entire squat.

- Hips & chest rise at the same rate on the ascent.

Tuesday 25.02.20

When is a box jump a box jump?

If you’re squatting, you’re probably squatting for a reason. Sometimes that reason is to get better at a sport, and that sport normally involved jumping. Basketball, you want to dunk. Rugby, it’s the line out. American Football, wide receivers, defensive backs all need a great vert. So how can squatting help your vertical? Find out more in the article below. And when it comes to jumping, especially box jumping, try doing them like the guy in the video, this will show you just how good (or bad) your vertical actually is.

Fordy

The Two Best Exercises For Increasing Your Vertical Jump

Ever since I can remember, I’ve wanted a higher vertical jump. Whether that was due to ad campaigns such as the “Like Mike” commercials or the luster of seeing an elite athlete throw down a monster dunk, having a high vertical has been always glamorized.

But how do you actually go about increasing your vertical? The answer is in two parts:

- Increased force output – How much strength or energy can be applied to the ground

- Increased rate of force development – How quickly force can be produced and applied

The combination of these two is what allows someone to propel him- or herself from the ground to as high as possible.

These two variables are the answers to the question you vertically challenged folks have been asking for years. Since our answer is in two parts, let’s take a look at both of these aspects separately and then bring them both together.

Increased Force Output

This sounds simple. It just means you should get stronger.

But strength acquisition is a topic that can be overly complicated and drawn out all on its own.

So we will look at the most simplified method. Given our goal of increasing vertical jump height, we will focus specifically on lower body strength.

When developing lower body strength, the king of exercises is the back squat.

Specifically, the back squat at a depth below parallel. Squatting below parallel with high loads has been shown to reap the most benefit in the vertical jump.

A 2012 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research took 59 participants and placed them in a ten-week training group focusing on three variations of the squat: back squats, deep front squats, and partial range of motion back squats. Beginning the training program, each participant underwent a series of tests including vertical jump, one rep max (1RM), and rate of force development.

The participants placed in the deep front and deep back squat groups improved performance in the vertical jump by just over one inch.

The partial squat group showed no improvements at all.

In addition, each group tested the three squat variations for improvements in 1RM strength.

Results showed the deep squat groups demonstrated improvements in all three variations, but the partial squat group only improved in partial squats.

The last test, rate of force development, was not changed within the deep squat group, but was significantly decreased in the partial squat group.

Through this study we are able to see three important points:

- Deep squats improve vertical jump height

- Deep squats increase force output no matter the range of motion

- Partial squats actually decrease rate of force development

So, we now know how to develop variable number one – force output. The research shows squatting deep can increase vertical jump and force output.

Now, how do we go about increasing the second variable, the rate of force development? I want to increase my vertical more than one inch.

And I know if the force I can now produce is developed more rapidly, the amount of power produced increases dramatically.

Rate of Force Development

Simply squatting deep does not help with increasing the rate at which force is developed.

Deep squatting is primarily affecting the musculature, but in relation to power or rate of force development, we need to train the nervous system. This means we must focus on recruiting more of the high threshold units. These motor units are most easily recruited by increasing load while simultaneously trying to accelerate that load as quickly as possible.

Olympic lifts are commonly used to recruit these high threshold motor units are the Olympic lifts. However, since these lifts are more complex than many other exercises, technique can limit the progress made.

In order to avoid the technique issues, I suggest focusing on a simplified derivative of the clean – the mid-thigh pull.

The mid-thigh pull starts in the same position as the hang clean and requires triple extension of the ankles, knees, and hips, yet does not require the catch that a clean does.

Since it is so simple, you can focus strictly on adding weight to the bar, accelerating it upward as quickly as possible, and then letting the weight fall.

Some studies have even shown that in reference to our primary goal, increasing rate of force development, the mid-thigh pull is better than the power clean. A 2011 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research compared the power clean, hang clean, mid-thigh pull, and mid-thigh power clean.

The comparison showed the mid-thigh pull to be the superior means of increasing rate of force development.

Putting It All Together

So we’ve found exactly the combo of movements we are looking for: the best method of increasing force output (deep back squat) and the best method of increasing rate of force development (mid-thigh pull).

In order to program these two exercises, we will use the concept of linear periodization, which also happened to be used in the squat depth study.

These exercises can be done up to twice a week. Any more than that starts to challenge recovery, which can negate any progress. They can also be done within any training program.

The only requirement is that these exercises be done early in your workout, since they require force and/or power and any fatigue will inhibit this program’s effectiveness.

Hypertrophy Phase:

- Mid-Thigh Pull 4 x 5

- Deep Back Squat 4 x 10

- Rest Break: 1.5 minutes

- Phase Duration: 4 weeks

Max Strength Phase:

- Mid-Thigh Pull 4 x 4

- Deep Back Squat 5 x 5

- Rest Break: 2.5 minutes

- Phase Duration: 6 weeks

Speed Strength Phase:

- Mid-Thigh Pull 4 x 3

- Deep Back Squat 5 x 3

- Rest Break: 3 minutes

- Phase Duration: 4 weeks

Power Phase:

In this phase, alternate one set of exercise one with one set of exercise two.

- Mid-Thigh Pull 5 x 3

- Deep Back Squat 5 x 3

- Rest Break: 3 minutes

- Phase Duration: 3 weeks

Monday 24.02.20

We’re so sorry but Fordy has messed up the site. He tried to update some bits and as a result crashed a few other bits instead, including the Leaderboard so we’ve have to fix it behind the scenes. Normal service will resume in the next 48 hours.

Fordy (My Bad)

Respect Greatness

Sometimes you learn a lot just by watching, and who better to watch than Lu Xiaojun. If you don’t think warming up is important then watch the video. If you think you’re to old to squat, then watch the video. If you don’t think that mobility is perhaps one of the most important aspects to your squat, then watch the video. In fact, just watch the video.

Sunday 23.02.20

SEEN THIS BEFORE

We’ve discussed quite a lot on Ankle Mobility and Range of motion, but, I love these videos and I think they allow you to see it in a different perspective. If you’re not working on ankle mobility then take today to go back over some of the older posts and start to look at it. It won’t just affect your squat mobility in the gym, it will also make everything easier in your everyday life. It’s five t ten minutes a day, just get it done.

Fordy

Four Telltale Signs That You’re An Athlete

Start the debate in 3,2………………………1

I used to think the athlete gene skipped me.

I grew up in a family that always prioritised sports and athletic activities. My mom always found time for exercise, and my dad is an endurance athlete and continues to do everything from skiing, to 50+ mile bike rides, to kiteboarding and more. Both my siblings excelled at sports in high school, and my brother even played college basketball.

I played sports in high school, and although I was never bad at basketball or soccer, it was also clear that neither was my calling. So when I went off to college I gave up all sports and anything even remotely athletically-related, resigned to thinking that I would be a weak, uncoordinated, non-athletic person for the rest of my life. And even when I got over that foolish belief and became a personal trainer while living in Amsterdam, I remained unconvinced of my athleticism and was constantly worried people would see through my facade and realise the fraud I really was.

Luckily, although it’s taken years longer than it should have, these days I finally believe deep down that I truly am an athlete.

In fact, I strongly believe that everyone is an athlete.

If you’re thinking, “no way Krista, I am definitely not an athlete,” trust me, I know how you feel—and I refuse to believe you. If you feel this way, you just haven’t discovered your potential as an athlete—yet.

But if you’re finding more and more that you’re actually enjoying your workouts and get excited to work on new skills like handstands, pull ups, or whatever your current fitness goal is, congratulations—you have officially embraced your inner athlete.

Here are four telltale signs you know you’ve finally embraced your inner athlete:

You Care About Performance More Than Appearance

When I used to only work out just to try and lose weight or work off last night’s pizza, my only focus was how my jeans fit and how small the number on the scale was. Sure, I always had somewhat of a competitive side and would always try to work harder than everyone at spin class or run faster than the other joggers around me, but ultimately what I really cared about was my appearance and health.

Yet as I got more into HIIT and became interested in sports like boxing, Krav Maga, and bodyweight training/calisthenics, something slowly started to shift. I began to work out not just to feel confident in my own body, but to get better at my sport. I became less concerned with the scale and more about how my workout would make me a stronger, better athlete.

So when you notice yourself caring more about how your workouts will affect your sport or fitness goals rather than how many calories you’ll burn, you’ll know you’ve officially embraced your inner athlete.

You Focus on Building Skills (Rather Than Just Getting Your Workout Over With)

Like most people, I used to absolutely dread my workouts (especially when running was my only form of exercise). At that time, my entire focus would be on getting my workout over with—the sooner I could be done with it, the better.

But as I started to have more and more athletic and fitness goals and began wanting to conquer cool exercises like handstands, pistols, and gymnastics skills, something changed. My workouts started to feel more like play time, a time to experiment and see all that my body could accomplish. They became less torture and more fun.

If this sounds crazy to you, just try and think about something you enjoy and how it seems to transport you to a space where it feels less like work and more like fun. It could be anything—dancing, ultimate frisbee, rock climbing, skiing, you name it. We’re all good at different things, so don’t limit yourself to the belief that you’re only an athlete if you’re good at traditional sports like football or basketball.

Because when you start wanting to build skills or get excited about working towards a cool fitness goal, no matter what your current level—you’re officially an athlete.

You Start Treating Food as Fuel

I’ll be the first to admit that I used to treat calories as the ultimate enemy. Back when I would work out just to lose weight, I had an extremely unhealthy mindset that the less I ate, the better. In my mind, food was evil, and the less calories I consumed, the better of a person I was.

Obviously, this is an extremely unhealthy take on food and I hope that all of you are smarter than me and have never had such a negative relationship with food. Yet the ironic thing is that once I started treating food as fuel for my workouts and life, not only did I actually get to eat more than ever, I was able to maintain a level of leanness I never could before.

So that moment that you start thinking of food and how it will affect your workouts, your mood, and your mental sharpness, that moment when you embrace food as the way to getting stronger, fitter, and more athletic—that’s the moment you know you’re an athlete.

You No longer Look Forward to Rest Days

Like most people, rest days used to be my favorite days of the week. I would look forward to not working out, being lazy, and pretty much not moving all day long.

But two things started to happen:

First, I started to actually get disappointed that I wouldn’t get to work on whatever skills I was currently focusing on. This was a completely new concept to me, that a person could actually look forward to their workouts and regret the days that they couldn’t work out.

Yet as I came to accept more and more that I really was an athlete, this began to make much more sense. When you have a goal and something to work towards, it’s much harder to take any time off (though it’s absolutely necessary, so don’t skip it).

Second, I started to miss the mental and physical benefits I got from my workouts. I realised that on days when I worked out I felt clearer headed, less anxious, and more confident. I felt like I could deal better with any tough thing that came my way, and nearly always felt less stressed and more energised after my workout than I did before it. I realised more and more that my workouts had become a sort of meditation for me, a chance for me to feel “in the zone” and forget about anything else I had been worrying about.

So when you start looking more forward to your workout days than your rest days, you’ve officially embraced your inner athlete.

You Are An Athlete

No matter what your current fitness level, you are an athlete.

If you move, you’re an athlete.

If you try, you’re an athlete.

If you think you’re an athlete, you are one.

“If you have a body, you are an athlete.” – Bill Bowerman, co-founder of Nike

https://www.12minuteathlete.com/you-are-an-athlete/

Saturday 22.02.20

Don’t force your fitness in 2020

With so much information now readily available about how short term fixes aren’t the best solution for your diet, and quick fixes like magic teas or restricting calories to super low levels don’t work, we are forever being advise to take on an approach that is sustainable in order to create or form new habits that could be with us for life and not just for periods of our lives. It does make me wonder though why we still do the exact same thing when it comes to our fitness, especially at this time of year. We get the urge to jump back into the gym or the buy into the latest trend by sitting on a bike in front of a screen smashing out a workout into every spare minute of the day we can find. This kind of dedication and determination is admirable until we spend the next 3-weeks of the month complaining about an injury we have picked up or the severe muscle soreness we are now experiencing every time we get up off the sofa or walk down the stairs. It’s then that we realise that this kind of intensity isn’t sustainable, it’s akin to the crash dieting that seemed like such a good idea at the time until a few days later when I’m moody, irritable, lacking in energy, tired all the time and hungry!

So why all of sudden are we ok to accept that playing the long game with our nutrition is ok, but not with our fitness. I have to laugh when I hear people ask about gym memberships and say things like, “I don’t want to be tied in for 12 months”, or “do you do 3-month memberships”. If you believe that you are going to go to the gym for 3-months, what are you going to do in the 4th? Or what about, “I’m buying into the 12-week challenge, I’m going to transform my body in the next 12 weeks”, what happens in week 13, 14, 15? Stop making the grand gesture that’s often empty and realise that ‘Consistency Trumps Short Term Intensity’ in pretty much everything you do. You need to start to realise that it doesn’t matter what you do, it’s going to be more about how long you do it for. Think about the people in the gym who have the physique that you are aspiring to, and then ask them how long they have been working out for, I’ll bet you the answer isn’t 12 weeks. On the odd occasion that they have been ‘cutting up’ for 12 weeks, they usually like to tell you that they have been training for years though to get like they do. It’s the same with anything in the gym, the person who’s slaying the rest of the spinning class just so happens to be there every time you are, consistency.

So, look at the long game, look at a way to keep you focused over a long period in order to give yourself the time to create a habit out of the gym without the pressure and stress of diving into a high intensity short fix routine. And if you can’t go for some reason or you miss a class, so what. The world isn’t suddenly going to end and you’re not going to lose all you gains either. Create an environment that is always changing, even die-hard athletes fall out of love with the ‘game’ due to the repetitive nature of doing the same thing over and over. I guarantee that the threshold for an everyday athlete like you and I is way less than what theirs is, so sitting on your bike in front of the TV screen maybe be great for 3 months, 6 months, but what is that experience going to be like in 12, 18 months, are you still going to be ready to strap yourself into the pedals? Some will, but a lot wont.

Molly Galbraith put it perfectly, “It doesn’t matter if you don’t get to the gym today, it really doesn’t even matter if you get there tomorrow. What matters is that you’re still in the gym 20 years from now”

2020 should be about finding your fitness and not putting stress on yourself to overly commit. Consistency will come, just don’t force it.

Fordy

MUSCLES, LEG MUSCLES EVERYWHERE

In this last article on the squat, we will look at how different depths, foot position, and bar position affects muscle activity of the lower limb. To determine what muscles are active during the squat or for any exercise for that matter, researchers use a device known as “Electromyography” or EMG. EMG evaluates and records the electrical activity of skeletal muscles. The squat is a highly versatile exercise that can target specific muscles groups for both performance and rehabilitation purposes. Having a knowledge of how squat variants, affect muscle recruitment patterns, can assist FTI instructors to modify the squat, to target specific muscles during both rehabilitation and strengthening programs.

Calf muscle

EMG research which has investigated calf muscle activity and force during a squat has observed a moderate amount of calf muscle activity during the squat. Calf muscle activity (Gastrocnemius) increasing as the knee progressively flexes more on the way down; and decreases during on the way up, as knee extension increases (Escamilla 1998). Calf (Gastrocnemius) activity appears to peak between 60 to 90 degrees of knee flexion; to eccentrically control the rate of ankle dorsiflexion during the descent (Escamilla 1998). Finally, positioning the feet directly under the hips during a wall slide squat has been shown to increase calf muscle activity (Blanpied 1999).

Quadriceps

During a squat, the quadriceps are the prime movers, particularly the vasti muscles, which show significantly higher activity than the rectus femoris. Peak quadriceps activity occurs at 80-90 degrees of a squat, with no further increases with greater knee flexion (Escamilla 2001). This data indicates, half squats (to 90 degrees of knee flexion) will maximize quadriceps activity. Descending beyond 90 degrees of knee flexion, which is near the parallel squat position, may not enhance quadriceps development (Escamilla 2001). Finally, when compared to wall squats with scapular support, appears to increase quadriceps activity (Blanpied 1999).

Vastus medial Obliquus (VMO)

The vastus medial obliquus muscle is the most distal segment of the vastus medial muscle. Its specific training plays a major role in maintaining patella position and limiting injuries to the knee. Weakness, timing, and dysfunction of the VMO causes mal-tracking of the patella and subsequent damage to surrounding structures which leads to increased forces on the knees, often resulting in injuries (Lefebvre 2006). Furthermore, imbalances between vastus lateral and VMO enhances the risk for patellofemoral pain (Karst & Willit, 1995). This data demonstrates the importance of early VMO training following a knee injury. Research on VMO activity during a squat shows the VMO contributes 30.88% to the activity of the thigh during the partial squat; yet, it contributes only 18.85 and 20.23% during the parallel and full squats (Caterisano et al., 2002). Other research (Anderson et al., 1998) has investigated if widening the foot position during the squat; affects VMO activity relative to VL activity (VMO: VL ratio). The researchers found a wider foot position did not increase VMO activity. However VMO was more active throughout a 90° range, and increasing knee flexion angles can increase the activity of the VMO relative to the VL. Taken together, these findings suggest squatting to no greater than 90 degrees of knee flexion; may be the optimal squat depth for VMO.

Hamstrings

The hamstrings due to their biarticular nature (crossing both the hip and knee) act eccentrically during the descent, and concentrically during the ascent. However as the knee flexes during the descent, the hip flexes, the length of the hamstrings is maintained throughout the squat; resulting in minimal change to hamstring length. This may increases the length-tension relationship in favor of force production (Escamilla 2001). Research suggests hamstring activity is greatest during the ascent phase of a squat and is strongly related to weight lifted (Wilk et al., 1996). In contrast, during a bodyweight squat, hamstring activity is minimal, and not significant until loads of 12 RM loads are used, presumably to enhance knee stability. Hamstring activity during a squat; reaches peak activity between 50 – 70 degrees of knee flexion. Finally, researchers (Blanpied 1999) observed a significant increase in hamstring activity when squats are performed in a squat hack machine and when performing a wall squat with scapular support with the feet position forward of center mass. Interestingly, both deep squats and half squats appear to stimulate hamstring activity equally. Taken together, these results indicate that the hack squat, the wall squat with scapula support, and both deep and half squats effectively stimulate hamstring activity.

Glute Activity

Research which has investigated the effects of squat depth on gluteus maximus activity have found that gluteus maximus activity increases with depth (Caterisano et al., 2002). However, these results appear to vary with different loads (% of 1RM). Other researchers have found Gluteus maximus recruitment may increase with increases in squat stance width. Finally, Aspe and Swinton, (2014) analyzed the back squat and the overhead squat and found; the back squat elicited greater gluteus maximus activity than the overhead squat. Interestingly, when compared to the front, full, or parallel squats, squatting at full range, did not elicit greater Gluteus maximus activation, suggesting either front, full, or parallel squats are equally effective exercises for Glut development (Contreras et al., 2016).

In conclusion, the results from these studies suggest the squat is an excellent exercise to strengthen the musculature of lower limbs. Also, muscle activity during a squat can be affected foot position, depth, support, and load. Notwithstanding any limitations from these studies, including differences in prescribed training loads, the following generalizations about muscle activity during the squat can be made:

- To maximize calf muscle activity prescribe squats to the parallel thigh position and position the feet directly under the hips.

- To target the quadriceps during a squat, prescribe squats to the parallel thigh position, for rehabilitation prescribe wall squats with a support pad placed at hip level.

- When targeting the VMO, prescribe squats to the parallel thigh position.

- When targeting the hamstrings, prescribe either deep squats or squats to the parallel thigh position with a minimum of 12 RM loads to equally stimulate the hamstrings. When prescribing a body weight squat, prescribe a wall squat with a support pad placed on the scapula and with the feet forward of center mass.

- When targeting the Gluteal muscle group, it is equally effective to prescribing a squat to the parallel thigh position or full range. For variation, front squats to the full range can also be used to stimulate gluteal muscle activity.

- Dispite differences in muscle activity, full range of motion squats are still an affective variation of the squat for general strengthening and athletic development.

https://

Friday 21.02.20

“When the standard changes, So does the performance”

I’ll be honest, I kind of needed this video today. Yes, it’s a little motivational for my liking. Yes, it’s often heard and then often forgotten. But the one line I loved in it was “when the standard changes, so does the performance”. And that is exactly what I want the Bracket to be known for. So many people train, but train with no real intent and when someone suddenly asks you to do something different from the ‘standard’ their performance has to change. I love that sentiment and we want to keep changing the standard so that your performance has to change as well. If we succeed in doing that, then I will have succeeded in my goal as well.

Fordy

What the best do better than everyone else

Success is made in the mud, it’s in the dirt. It’s the grimy work that no one else wants to do for countless hours that leads to success. When the world looks at success they see the small percentage of the effort and workload that has gone before to create it. Think about this, 95% of the work you do will never be seen but you will need to do it if you want to succeed. A footballer will train everyday each week, spending countless hours learning to bend a free kick over a wall time and time again. In the match on Sunday he gets put into a position, when in a single stirke of the ball he will have to use all the skills he has spent countless hours cultivating but what the crowd will see is the 2 or 3 seconds as the ball leaves his foot and hits the back of the net. Here’s another example from a great book called ‘Training Camp’ by John Gordon. What is the difference between a baseball hitter that has a 350 average and a 250 average over the course of a season? Apart from millions of dollars in wages and endorsements and the fact that one would be seen as an elite player while the other just a member of the team, when you break it down into the number of games played it equates to an extra 1.6 hits per week. That’s it! 1.6 extra hits a week. That’s what the best do better than anyone else.

A lot of people say that being average isn’t an option for them but in reality spend their life being average or good at something as they never strive to become great. The reason for this isn’t exactly complicated; in fact it’s very simple. To be great or the best you have to have a willingness to be uncomfortable. If you’re always striving to get better then your always growing, and if you’re growing then you’re not comfortable. You need to embrace this as part of a much larger process, you need to be willing to pay the price of success and for some the price is just too high.

When asked, what’s the secret to their success? Some of the most successful people in the world give an unexpected answer. We want to hear that there is some magical formula, a secret recipe, when in reality most simply say that they work hard, focus on the fundamentals, stay positive and had the desire to succeed and make an impact in their given area of work. It is these characteristics that are shared by some of the very best athletes and businessmen/women in the world, and allows them to become the best of the best.

There is though a formula to success and over the next few blogs I am going to be sharing it with you. Bit by bit we will create the formula that leads to success, which in itself is predictable, repeatable and understandable.

Mountain Top Moment

Someone will have paved the way already in your area of expertise someone has already shown you what success looks like. It could be someone you know, a complete stranger or someone who is already regarded as being the best in your industry. Most of these people have been doing something that they love for a long time and then had a moment when they realised they could actually become great at it. Others had settled for mediocrity, they have settled for something they were good at, written down goals because they had been told this was the way to achieve greatness but actually had nothing to do with what they truly wanted. When you see what you want and even how difficult the journey is to get there you will have the commitment, passion and energy to fuel you through your journey to pay the price and overcome the challenges to realise your goal.

The best of the best don’t only know what they want; they want it more than anyone else. They have more desire to succeed. How can you measure desire though? It takes more than thoughts and wishes, you can wish for something 24 hours a day, 7 days a week but if you’re not taking the initiative to make it happen then it doesn’t matter how much you wish for something. Desire is measured by actions. If you ask anyone right now if they want to be great the answer will always be yes. The difference is that the best don’t just think about their desire to be great, they act on it. They have a high capacity for work, they do things that other people wont do in order to succeed and they spend more time doing it. When everyone else is sleeping the best are busy improving by thinking and practicing.

Everyone has a calling in life and whatever that calling is, you should do your best to be the very best at it. To deny being your best was to deny the gift you were meant to give others.

The best want it more.

Wednesday 19.02.20

HOW TO SQUAT PROPERLY TO GROW YOUR BUTT!

I literally have NO words. I’m just going to let you watch the video and then make your own mind up.

Fordy

SPREAD THE GROUND

I love this simple little cue that coaches would do well to use for a lot of their clients when it comes to squatting. The engagement of the nervous system via cueing makes a huge impact on the muscular system especially during the squat. Remember, we train our mind in the gym as the mind ultimately controls the body. Give it a try.

Guide in maintaining tension in the hips and glutes during a squat

Movement-Rx movement coach and resident video guy is also a member of the CrossFit L1 Trainer Seminar staff as well as the CrossFit Weightlifting staff. Here’s a great cue to make sure you’re maintaining tension in the hips and glutes as you squat.

For those of you who lose tension in the hole, this one is for you!

We often hear powerlifters use the cue “spread the ground!” For me, this cue from Ingrid made much more sense to explain what we are going for.

One of the best exercises that you can try whether you are trying to lose weight or build muscles is squat. It is one of those exercises that is hard to do properly but the results are going to be amazing once done correctly.

In the squat, it’s super important to keep the glutes engaged. Yes, that’s true! This cue has worked wonders for a bunch of my lifters and hopefully it will help you, too.

Step 1: Set your feet by pressing your big toe into the ground. This will help keep your feet rooted throughout the whole foot.

Step 2: Imagine pulling the heads of your femurs sideways out of your pelvis. If you do this correctly you should feel the side of your butt firing.

Step 3: Initiate the squat by continuing to spread your hips sideways and sit straight down. If you are pulling sideways, your butt will automatically sit down and back. Remember we don’t want to send our butt excessively back as we’ll lose our upright torso.

Step 4: Maintain tension all the way into the hole and accelerate back up.

Give it a try. You should feel much more solid and will be recruiting more musculature… and hopefully move more weight!

Tuesday 18.02.20

INTENSITY

One of the biggest mistakes we see all the time is when people mix up volume and intensity. They think that the more they do in terms of the number of reps the higher the intensity of the workout becomes. This has been due to the rise in ‘High Intensity’ classes and training formats that mistake the length of a WOD or workout with the level of intensity. Jumping once onto a really high box using maximum effort is high intensity, even if I do nothing else afterward. Training balls out for an 20 minutes though on a WOD, although ‘intense’ isn’t necessarily at high ‘intensity’. So to clear this up once and for all here is a great video by the beardy man again and a great article from Barbend. If you’re still confused after this, then read it again and watch it again until you’re not.

Fordy

There is a maxim in the coaching world; you can train long or you can train hard, but you can’t train both. There are strongman coaches in both camps, and I will attempt to show you the difference and help you pick the right style for your body and schedule. I will begin by clarifying what each style means.

Training for Volume

When an athlete trains for volume, they attempt to do as many sets and reps of an exercise or muscle group as they can in a training session. These sessions generally take a minimum of 90 minutes and can go on for two or three hours. An example of this type of session would be:

- 10 sets of 3 rep squats

- 10 sets of 10 stiff leg deadlifts

- 10 sets of walking lunges

- 3 sets of tire flips

- Sled drag

- Plyometric jumps

As the amount of sets and reps add up, the ability of the body to perform at its peak diminishes. By the end of a workout like this you will exhaust every muscle fiber in your lower body and barely be able to walk out the door. You can crawl out of the gym and declare, “EPIC leg session! Killed them!!!!!” It will take the full 72 hours for recovery and often the athlete will not do another leg session that week.

The principal behind this style of training operates on the notion of breaking down the entire muscle group and letting it build back up over time. Being in the gym for long hours, they get out their frustrations, love the feeling they get, and have all their bases covered when it comes to training a muscle group. Many bodybuilders follow this style of training as it can be effective for muscle building, especially in trainees who have increased recovery ability.

If you only have a few days during the week to train, but a good amount of time to train on those days, you may want to consider a high volume program.

Training for Intensity

Conversely, when an athlete trains for intensity, sessions will be brief and near a max all of the time. An athlete may only do a few work sets in a session but train every day, even multiple times per day. This idea (started by Eastern European coaches) focus on the body adapting to the work in a few hours and becoming wired to do exactly the same thing every day. After a brief warm up, a sample session may look like this:

- Squat 2×1

- Jerk 2×3

- Farmers walk 1x75ft.

Session B:

- Good Morning 3×3

- RDL 3×2

- Box Jump 3×2

To understand this program completely, you would see a very similar day two, three, and so on. For a set period of time the athlete works on achieving a PR nearly every day. The athlete should never be exhausted after a session, but instead feel the effects of a few short heavy sets. The recovery time is cut to hours instead of days for this training. Your schedule must allow you to train every day, and multiple times per day is actually preferred.

What is the main difference in the simplest terms?

Recovery and optimizing your down time is at play here. Intensity plays off of the idea that a muscle is either recovering or tearing down. It is rarely ever at stasis. It does just enough to stimulate growth and then stimulation is reapplied as soon as recovery is repeated. Volume is more forgiving in what happens to a muscle. Allowing more recovery time to heal from greater damage, it seeks to do more at once. That is, volume digs a hole with a shovel and intensity digs with a spade.

If you have the time for multiple short sessions per week, it would be wise to go with intensity. The quality of all the reps will be better and you should make more significant long term gains. You also have an advantage of truly getting comfortable with max weights. This decreases the chance of misses.

Volume disciples can’t be in the gym every day. You would be so worn down that you never fully recover. Often times, a Monday squatter with presses on Wednesday will be working off spongy legs yet, and lose a bit off their power in a press. Many times though, they do not have a choice. Hitting a low volume program just three days a week will not provide enough stimulation to provide consistent progress. Sometimes a mix of the two may work for you. A 12 week program of such can be found here.

Make sure the amount of work you do matches what your body and schedule can work with. Serious athletes often rearrange their work lives to make sure they can hit the gym daily. It comes down to priorities. No matter what style of training you pursue, make sure you use proper technique and work to the best of your ability.

Monday 17.02.20

FRONT VS BACK

Just because it’s squat month, and by that we mean back squat, it doesn’t mean you probably won’t be doing other variations of squatting as well. The most common one is the Front Squat. But why is it that you can lift more weight on the back squat that you can on the front squat? The guys at Squat University explain all in the video. Let us know if you know anyone who has the reverse.

Fordy

Sunday 16.02.20

I A Peeeeeeeeeeeee

That stands for INTRA ABDOMINAL PRESSURE. This is a foundation when it comes to good squatting. The guys at JTS in the video go through it in a really informative manner with some simple, great cueing to make sure you get that mid section tight in order to get your squat right.

Fordy

BREATHING IS NOT BRACING

Video Transcript:

All right. Thanks, everyone. I do appreciate you guys taking the time to come in today to listen to this piece. It is an important piece and it needs to touch on because I see this Facebook and there’s somebody with an article or usually a video talking about, and almost some time I’ve seen it labeled Breathing is Bracing, Breathing is Bracing. It is not bracing, so we need to kind of understand that there’s three functions to the diaphragm. We’ve got respiration function, we’ve got stabilization function and we’ve got my favorite, the sphincter function. We’re not going to touch on that one today, unless I have some really profound gas and you can all hear it. Outside of that, we’re not going to touch on it.

They are integrating together. When we talk about integration of those today, now I’m not saying breathing isn’t important. Breathing is a fundamental piece where you start. If you have respiration dysfunction, you will continue to need to go back and deal with issues. They’re going to come up. They’re going to pop around different places in your body. It is a fact that you will continue to have issues. You will have power loss. It is important that if you have breathing dysfunction, you must deal with it, and so that’s why we talk about the diaphragmatic breathing strategies. We’re not going to go in to that today. We’re going to say that’s taken care of. What we’re going to talk about, what is the difference between diaphragmatic breathing, proper breathing and the stabilization function that the diaphragm also has and how those integrate together. They are not the same thing.

Unless you guys want to talk about sphincter function, we can spend time talking about that. It would be fun. I know [Brandon asked it 00:02:28]. Before you do bracing, we got to talk about posture, so you cannot have proper bracing without having proper posture to begin with. It simply won’t happen. We must have the diaphragm right here, this cone-shaped muscle that hooks to the rib cage here and it drives down, working in opposition to the pelvic floor. These two have to be aligned, and we’ll get into why here in a minute, but this is why our flared rib cage position is a big issue. I used to walk around with this actually.

You’ll find my rib cage actually used to be flared outward and almost raised up until I started doing a lot of this work and it physically changed. That was something that was with me. I remember it like in high school because I would be like, “Man, I could never compete in bodybuilding. I’ll never have the physique because I got this weird jacked-up rib cage.” My rib cage changed in my mid-30s when I started doing this stuff. That is freaking crazy.

The other is this right here, and I’m one that has to deal with that. I’ve got some anterior pelvic tilt there and we’ve got to deal with cleaning that up. A lot of our larger muscle vectors will be in that position, but you’ve got to be able to fix that first because if we don’t have those two working perfectly in opposition to each other we’ve got this opened up here what happens if we fill it. We’re going to pressurize like you’re breathing. You’re going to fill it with air, so I’m going to push out towards the front and we need it to be equally pressurized all the way around.

Any deviation here is going to cause an issue. See this quite a bit like in squatting where people have either shoulder mobility issues or this tilt that just kind of start in this unhinged position right here in the squat. Guess what? They’re just going to over exaggerate, got some tilt, pressurize, definitely I followed all your stuff and I went in to the hole in the bottom of the squat and I went right in the butt wink just because you need to start here. Now, I can pressurize. That’s the beginning.

Any time, and let’s just call it an open scissor, we have that. We have to fix those deficits. Where do we start? We start with assessing breathing. You got breathing dysfunction? You’re going to have dysfunction in your body. You’re going to have energy loss. You’re going to have issues because if the diaphragm doesn’t know how to breathe properly, its other functions are not going to be working well as well. Next, then you go to posture. You got to deal to postural deficits.

This one here, when we talk about why is it important that it’s all the way around it uneven. This is where we start getting in to bracing functions and what does that mean. The difference between breathing and bracing. Breathing, you’re just filling with air, oxygen, so you can fill your body. Bracing, we’re using all the structure all the way around is an outer sheath and it needs to become rigid and resist. Then, we’re going to push against it and those forces need to be equal in all directions all the way around. That’s another complaint I’ve got because a lot of people say, “Yep, I’ve got that. I go to yoga. I really got this breathing function down. Got this big belly breast, big belly breast. I’m a master of it.” When we do some testing and they have a significant dysfunction.

Why? It’s all going this way, right here. We need to be inflating all the way around into the pera-spinal. You get pain in your deadlift right off that floor a lot of times. People aren’t inflating in that para-spinal region. Right back in here, we need to be pushing out. This is where the belt is a good cue to fill that up. There’s issue, I think, last year I helped Stan Efferding a lot with on his deadlift. He has experienced a lot of back pain and we did some quick fixes, focused on filling those areas up. Pain dropped down immediately. Power output went up.

This is an area how we find those deficits. You need to check around and find where am I soft at. This is something, like I said, that a lot of areas if we go back to class school stuff, I think yoga is probably right if we go way back. It’s just the way that some teachers, some instructors, so it’s not a job at yoga in general. It’s just an example of what I’ve seen with some people, which is not indicative of the whole.

We get back into, if we go into fighting. A lot of our classical sports like Muay Thai, jiu-jitsu, stuff like that, they have a lot of content on basically breathing and bracing type issues and that’s why it’s really important because that’s where, again, we wan to talk about that, one, both our posture and the fact that we need to be rigid. You need to be able to throw a punch. If I’m going to do something, you’re always going to be in this position. They’re going to be in, I’m going to get into great bench press position. That’s where I get the most pressing power with this fist. I’ll fight you all day long. That’s not the best position for power transfer.

Simply put, you know it. Let’s get to fight, come on. You’re ready to take a punch. Some pretty important pieces there to understand. We talked about it. I’ve got a little example here. The hot water balloon. We got the strong and blown it up. It’s a tight, constrictive vessel and we’re working against that. If you’re not, we can just bend you up and wrap you up like a little play toy, which what do you want to be in your core, your center. Something that we can just sit up and twist up. It doesn’t have a tight, rigid outer sheath. This is the difference. This is bracing. Right there, you can’t tie that baby up. Really important thing to understand.

Look at your skeletal system. We have Halloween coming up, so we see skeletons all over the place. Take a look at them. Huge mass of structural bones. All this stuff everywhere. Right here in the middle portion, there’s nothing – just a thin bone connecting the top to the bottom. Where does that force to create stability come from? It all comes from right in here, in the torso.

I’ve recently, I’m going to leave the names out, but over the last few months I’ve been interviewed by several well-known fitness publication magazines and they call me up. “Chris, we need to talk, you’re the breathing guy. We’ve got some articles that we want to put together. Follow all your work.” I get on the phone. All right, been watching all your stuff. I’ve been a big fan for a long time.

The question is, do you breathe in on the way down on a squat or do you breathe out? I don’t know. Give me some context. It depends. Do you breathe in between reps and then hold? How many reps do you hold before you breathe? I don’t know. It depends because we’re using the diaphragm for both respiration and bracing.

Think about it as a dial. If you’re going to run marathon, you’re going to need a lot of damn oxygen. Bracing isn’t going to be that critical. You’re going to crave for that dial down and you’re going to be using very little of the stabilization function. You start doing a MetCon. You’re in CrossFit. You don’t see MetCon. There’s going to be some requirement for stabilization, less for breathing but still a fair bet.

Do a 120 rep around squats. You’re going to be needing to breathe like pretty frequently, but you still need to brace, so you might be holding it for different pieces of that. Doing a 5 rep max or a 3 rep max. You might hold your breath for like two or three reps then catch your breath. Do a max single, you’re going to breathe once. Do a max double, you might still just breathe once. Let’s say you’re doing some intensive kettleball swings. You might be breathing on both functions just because the amount of oxygen intake. You might have to learn to mix those strategies.

Where you at? Well, me, I’m Chris Duffin so mine goes to 11. I don’t know. Those dial is messed up, 10 for all you. I crank it to 11. That’s where you are at. It depends. We’re using both functions, but this is why… I brought up the MetCon as an example. This is why we don’t want to do basic core loaded human movements to fatigue failure. It’s simple. You want to use up the breathing respiration function and your diaphragm is fatigued. What’s going to happen to your bracing? What’s going to happen to your back? Because you’re in a heavy loaded core movement. We don’t want to mix those two. You want to make sure that we’re not doing that type of movement when we’re going to be failing on the respirations front.

That’s what we talked about integrating those two functions together. There is no answer. I can’t tell you if you’re going to do a 5 rep squat, what that looks like for you. If you understand that it is a spectrum and where you need to fit on that spectrum to get those bracing functions align, that’s what we need to do.

I’m going to digress and jump a little back into bracing function again for a couple other reasons. When we talk about that rigid outer sheath, let’s talk about a training perspective. Like I said, we need to train that. Does that mean we need to do ab work to develop that outer sheath? No, it doesn’t. It actually means we might need to use the difference. One of the ways that we do assessment, I’m looking at that structure, is to get in a brace function and look to see if we got any [inaudible 00:14:29], any lines, big tight standing obliques. The hour-glass shape, the classical hour-glass shape. We do not want to see.

We want to see nice, smooth, rigid conformed. I’ve got those beautiful looking nice obliques and pointing down to the goods, we don’t want that showing up and being as prevalent. We don’t want those ab lines unless you’re like super… There’s going to be there because they’re muscle when you’re lean. There’s a difference between that and having that show when it shouldn’t be showing and having because that’s what is called. I’ve got a broomstick lying here in the background. How do we treat this function with hypertonic muscle? We’ve got to get it to relax. If we’re holding tension in these areas all the time, we got issues. We’ve got dysfunction.

I’m not a big lever in doing our typical flexion work for ab development. It is not just from the [inaudible 00:15:29] school of saying, well, that’s bad for loaded spinal flexion. Let’s not talk about that piece at all. Let’s talk about the piece of we’re training those two systems independently. Just like my big issue with doing hip, too heavy of hip thrusts is we get into some anterior tilt too much. We’re not able to get full hip extension. We’re still training to glut. We build a nice, big booty that it is in the integrated into the system core. We don’t have that athletic carryover because we’re not training the neuropatterns for this to work with a stabilized core. It would be grounded to the floor and transferring that power out.

Same thing if you’re doing loaded work. How’s the diaphragm actually working to inflate. It’s not. Again, this is why a plank, a rollout, stir the pack, but again a lot of people could be doing that strictly just ab based. You want to get in to that piece where you’re focused on making that rigid, your breathing into it, pushing against.

What did we have in that last slide? Pushing against our hot water balloon, that big outer. We want to make that outer sheath rigid and hard, but we need to be filling it with air. We need to be working both. On top of that, and I see this is a big issue in power lifting. People just want to work on the air side and I think that’s bracing. I think I get on the topic why that isn’t, but just creating a big flowy full of air. The biggest air possible in that bracing. You got one piece but not the other. Learn to work both together as a system. Then, once you’ve got that, figure out where you’re at on the dial.

Takeaways. Here’s what we need to focus on. Breathing dysfunction. If you’ve got it, fix it. Nothing else matters until you do. You will continue to have issues. Two, posture. You must have the correct posture before you brace. Bracing, we need to integrate both that outer sheath with having the correct posture. We already said filling with air working against it. Then, lastly, understand where you’re at, where you’re at on the dial. Breathing is not bracing. They are integrated. You must know how to do both for performance aspect and safety aspect.

Saturday 15.02.20

JOE ROGAN

I love this explanation by Joe Rogan about workout motivation (video). I think it depicts the way a lot of people feel about exercise and fitness and in general just working out. I also like the way that it has the images attached as I think lot of people will identify with what is being said and how it is being said in terms of their own relationship with working out.

Give it a watch and see what you think and if it relates to you or the other people around you.

Fordy

CONSISTENCY OVER INTENSITY?

With more and more people just training hard for the sake of it and WOD’s becoming increasingly more difficult, often for the sake of it sometimes it’s good to look at how consistent your training is rather than how intense it is. This is a great article courtesy of Joe Rinaldi (https://joerinaldi.blog/2018/03/07/consistency-over-intensity/) which covers it nicely.

I’ll be the first to admit – sometimes life seems tough, and that’s because it is. As I discussed in an earlier blog post the road to success is never linear.

“As a human being, I realize how important it is to understand that the road to success, no matter what the goal, is a rocky one. There will be bumps, there will be obstacles, and you may even trip and fall once or twice (or a hundred times), but as long as you never stop moving forward, you’re making progress and things WILL turn around. You may not see results day to day, week to week, or even month to month, but with persistence, perseverance, grit and a little bit of faith, progress is inevitable.”

This post is about how to stay the course when life gets tough and I’ll do my best to explain why I think it pretty much comes down to one word: consistency.

Before I continue I should note that while I discuss “bad days” in this blog, I am using that term to denote literal bad days as well as anything in life that is tough (adversity, obstacles, set-backs, mistakes, slumps, ruts, etc.).

I think most of us have an intuitive sense of what it means to be consistent. However, for the sake of being thorough, let’s define “being consistent” as adhering to something (principles, behaviors, etc.) over time (i.e. acting or doing something in a similar manner over time).

For some reason consistency seems to take a backseat to intensity in modern society and I can see why; consistency isn’t glamorous, consistency isn’t exciting and consistency sure as heck isn’t easy.

But, consistency is what gets results.

As a borderline gym addict, I feel that exercise is beautiful example of why consistency trumps intensity.

Let’s say it’s been a while and you decide that you want to get back in shape so you go to the gym for the first time in a while. You grab your gym clothes, head over to the gym, blast some – insert favorite music here – and put yourself through the most intense workout you’ve ever endured.

You gave it your all – you’re exhausted.

You get home from the gym, walk into the bathroom, take your shirt off and look in the mirror… and…. nothing – you look exactly the same as before your workout.

A bit discouraged you decide to stick with it and you crush another workout the next day. Again, you rush home to check for progress in the mirror and again… nothing – you look exactly the same.

You repeat this process for couple more days and still don’t see any results. Discouraged, frustrated and upset you conclude that exercise must not work for you – even though deep down you know that it does. Can you point out the flaw in this logic?

Exercise, like most things in life takes time and consistency to reap rewards.

The lesson here is twofold and applies to all areas of life, not just the gym.

- Intensity isn’t the answer. It’s consistency that gets us to where we want to be, whether it is in the gym, in the workplace, in school and anywhere else in life.

- Don’t give up when you don’t see progress. Change takes time and its imperative that you have faith, stay the course and keep grinding.

I think Simon Sinek does an excellent job of putting consistency into perspective in an interview with Tom Bilyeu of Impact Theory.

“It’s not about intensity, it’s about consistency…. if all you do is go to the dentist twice a year, your teeth will fall out. You have to brush your teeth twice a day for two minutes…”

– Simon Sinek

If you’re interested in hearing the rest of Simon’s interview, I would highly suggest checking it out here.

If the importance of being consistent still hasn’t quite clicked, I’m hopeful that this math analogy will make some sense. Don’t worry, I promise this is some pretty basic math that everyone can appreciate.

On a graph with a lot of data points (days), we can see that some days will be better than other and that over time, we can create a line that best matches the overall trend of our days.

If we take a close look, we can see that the line is an average of all the data points (days). In other words, the overall trend is affected by the sum of all of the data points (days) not just one by itself.

If you haven’t gotten the point yet, let me be about as straightforward as I can.

One point can’t define the slope of a line.

Using the line analogy, we can put bad days into perspective. We all have bad days. We all make mistakes. We all face obstacles.

But, those bad days don’t define us. What defines us is what we do in response to those tough days. What defines us is what we do day-in and day-out. What defines us is our action over time. So no matter what happens. No matter how bad of a day you had. No matter what you’re dealing with.

Keep moving forward, accumulate those “good days” and trend upward.

While I know this is all easier said than done, here are some things I’ve found helpful for shaking off a tough day.

- Know that growth, change and results take time. Understanding that progress and change take time is one way to help put a single bad day (or even string of bad days or weeks or even months) into perspective – we are defined over the course of an entire lifetime – don’t let a few bad days, weeks or even months hold you down.

- Believe in what you’re doing. If you truly believe that what you’re striving for is worthwhile, commit yourself and stay the course. Have faith and trust the process (shout out to the 76er’s).

- There are only two things we have complete control over in this life: attitude and effort. Wake up each morning knowing that you get to make a conscious decision about your attitude and your effort. Choose to have a good day. Choose to see the best in people. Choose to run the day and give your absolute best effort to everything you do.

- Use your support system; ask for help, its ok. Trust me, I’ve been there. I’ve been down in the dumps and I’ve felt like I was alone in my struggle and suffering. No matter how small or large the issue, problem, setback, etc., don’t be afraid to lean on your support network for a little or big pick-me-up; there is absolutely zero shame in that.

- On that note, if anyone out there (whether I know you or not) needs someone to talk to, or any encouragement, please feel free to reach out to me – I’d be honored and more than happy to help in any way I can!

Before closing, I feel that I should also point out that not only is consistency effective for making change, but consistency is admirable.

On the surface, being consistent seems pretty straightforward. However, beneath the surface, it becomes obvious that being consistent encompasses a host of other admirable traits – effort, commitment, dedication, accountability and perseverance just to name a few. Because of the deep-seated roots of what it takes to be consistent;

Consistency is comforting – people who are consistent are dependable and people like that.

Being consistent will not only earn you results but it will also earn you trust and respect. Being consistent is effective, admirable and as about straightforward as it gets as long as you’re willing to put in the work.

Being consistent is the simplest and surest way to get what you want. Whether it’s pursuing a concrete goal, trying to make a life change or just trying to be a better person, consistency over time is more powerful than anything else out there.

Having lived in Philadelphia for the past 18 months I feel obligated to incorporate at least one Rocky quote into a blog and there feels like no better time than now.

“Let me tell you something you already know. The world ain’t all sunshine and rainbows. It’s a very mean and nasty place and I don’t care how tough you are it will beat you to your knees and keep you there permanently if you let it. You, me, or nobody is gonna hit as hard as life. But it ain’t about how hard ya hit. It’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward. How much you can take and keep moving forward. That’s how winning is done!” ― Sylvester Stallone, Rocky Balboa

It’s not always going to be easy.

You’re going to get knocked down.

Get back up. Be relentless. Be consistent.

You will come out stronger on the other side.

Friday 14.02.20

MEET MR. MOVEMENT

If you haven’t heard of Ido Portal before, now’s your chance. He’s a master of movement, if you watch a couple of his videos, your first thought is often, ‘How the (expletive) does he do that?’ or ‘I’m pretty sure if I could do that, getting out of bed in the morning would be so much easier’. He has dedicated his life to moving better and as such he make the very difficult look effortless. Your aim should be to get close to the sort of movements he can do and practice them. Practice them a lot. Every joint will thank you for it (eventually) and you will soon be moving a little bit more like a ninja than you were before, and who doesn’t want to move like a ninja? No one right.

Fordy

MOVEMENT

This is a huge article, so apologies for that, but give is a read. It covers so many interesting trends in the industry that have forged fitness in the last 40 years or so. There is so much you will learn, so grab a beverage of choice and enjoy.

Bro, what kind of muscles you have?” asks Ido Portal in a short video introducing his philosophy. He’s barefoot and shirtless, his long hair pulled back as he tumbles across the frame and does handstand push-ups in the rain. “No—bro, what kind of patterns you have? Can you flip? Can you invert? Can you crawl?”

Portal has spent the past few decades honing a physical credo and method that’s now practiced by thousands of people all over the world—from office workers, to former CrossFitters, to NBA players, to the ever-controversial UFC titan Conor McGregor. Known as The Ido Portal Method, or simply “movement,” his approach purports to take the “most potent” parts from a range of physical disciplines by shedding the dogmas that often accompany them. As he puts it: “I want the contents, not the container.”